Give it a Rest: Embracing the Sabbath

The common refrain to the greeting "How are you?” is changing. While the response, “I’m fine,” still holds the number one spot, a new challenger is rising. Rapidly ascending the charts is the phrase, “I’m so busy.” A sigh of exhaustion often accompanies it. Yesterday, while visiting a local café, I overheard this exchange between two middle-aged adults as they bumped into each other while picking up the mobile orders.

“Hi, How are you?”

“Oh, I’m so busy.”

"Yeah, I know what you mean. It's insane with all the school startups."

“Me too, and my partner is out of town for a whole week.”

“I’m swamped.”

“Nice seeing you, gotta run.”

Is this or similar exchanges just part of a socially acceptable banter these days, or is it true that people are busier than ever before? I've concluded it's both.

Today, people are praised for their productivity, effectiveness, and accomplishments. People are also encouraged to have active and busy lives. Thanks to many of our recent technological inventions, people no longer need to experience downtime and boredom; that's out the window.

Years ago, I sat with middle school kids around a few picnic benches in New Hampshire. The lake before us sparkled from the sunlight of a bright blue sky day. We were waiting for the breakfast bell to ring so we could head into the dining hall. One of the girls had a downturned expression with her chin resting on her open hands. I inquired how she was doing, and she responded, "I'm bored." I smiled, looked out at the lake, and said, "Well, I'd enjoy it now cause life doesn't yield much boredom when you get older."

That evening, a campfire skit featured the line, "Jesus is coming, look busy."

But more than mere busyness, we also know the societal push is for us always to be doing something. Like you, I have that voice pounding in my head to do more, generate more, and work more. Yes, that voice gets me out of bed in the morning and nudges me. I'd not be writing this essay without that internal encouragement. But contemporary society's over-active work ethic and distraction monster have claimed too much psychic territory. Pharoah's voice from ancient Egypt is the voice to “do more, be more, see more, and create more.” That ancient autocrat echoing through the centuries tells me my value comes from building more pyramids. In that sense, we may all be in captivity still. Where is our Moses saying, "Let my people go."

Ancient people in the Near East seem to be the first to have realized and articulated the need to "give it a rest." They were enslaved people before becoming a nomadic tribe. While the Hebrew scriptures suggest that from the very outset of time, even Yahweh insisted on a day of rest, it wasn't until the Hebrew people moved toward a more settled existence that they finally got the message and encoded it in their first book of laws. Remembering the sabbath day became a commandment tied to other ideas such as the year of Jubilee, a time of debt relief every fifty years.

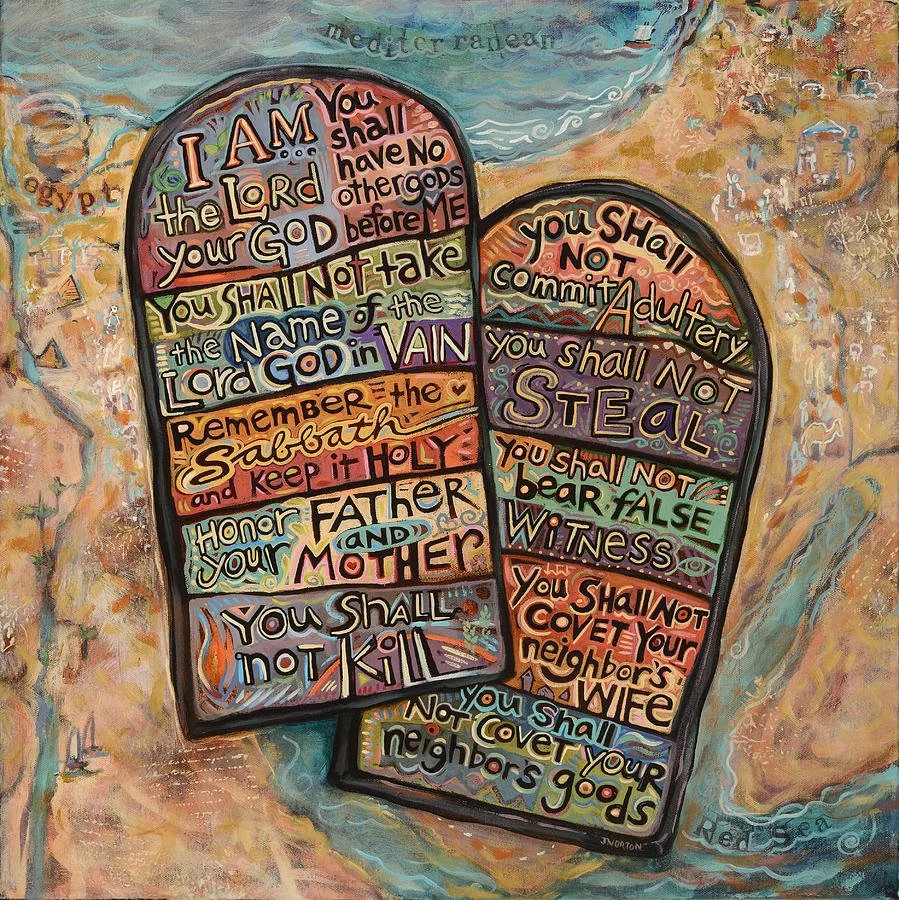

The fourth commandment, "Remember the sabbath day and keep it holy," sits as the lynchpin between the first three commandments about our relationship with God and the final six, which address our interactions. Is this an intentional design that might suggest that keeping the Sabbath leads us to healthy human relationships?

In our time, there is much gnashing and wailing around laws or structures that are no longer followed, but rarely mentioned is the one commandment our society seems quite broad to defy.

There was a period when external collective agreements reinforced the practice of the Sabbath. On the farm in Montana, the wheat farmers with Nordic piety never worked the land on Sundays. A classmate of mine from seminary discovered this while serving as a young pastor in a rural parish. As the farmers rested one Saturday afternoon, lamenting the coming storm and their inability to complete the harvest on time, my friend naively spoke up. "Why not finish the job tomorrow?" A look of dismay came over the men, and one said, "Oh, Pastor we would never work on the Sabbath." That happened thirty-five years ago and is a reminder of an era with culturally reinforced norms. That reinforcement disappeared long ago in our go-go 21st-century internet-connected society. The only way to reclaim Sabbath falls to the individual and perhaps a tiny cluster of friends and family members.

By Sabbath, I'm not speaking of a day off to finish errands. Instead, I wonder about time on the porch, a walk in the park, contemplating Mary Oliver's poetry, or extended reflection on life's big questions. The more extroverted among us might invite a friend to the porch, the park, or the conversation on those significant looming questions. Some Orthodox communities, be they Jewish or Amish, restrict engagement with all things mechanical and technological. Thus, it's a walk to the synagogue or the neighbor's barn for supper. These practices seem utterly distant, and the reader may think I'm casting about for a time that is simply out of reach—a fair point. I don't see our society legislating a sabbath day with a return to blue laws, and everything closed on Sabbath. No, if you want a sabbath, you must claim it for yourself.

Our restless times call for a response, and I don’t see more activity moving us further toward the realm of peace. Self-imposed pauses. Days of rest. Mindfulness practices or plain old prayers of silence are increasingly needed. I am stepping away from my phone more often. Don’t you long for this time, this pause, this break from the rat race?

As Walter Brueggeman points out in the quote below, finding Sabbath requires intentionality and communal reinforcement. It's not enough for us to seek Sabbath, though that is part of the solution. What is needed is a commitment by the community to Sabbath time. This might happen in gatherings where people say, "Let's pause from all this activity, even if for a moment, an hour a week.

“In our contemporary context of the rat race of anxiety, the celebration of Sabbath is an act of both resistance and alternative. It is resistance because it is a visible insistence that our lives are not defined by the production and consumption of commodity goods. Such an act of resistance requires enormous intentionality and communal reinforcement amid the barrage of seductive pressures from the insatiable insistences of the market, with its intrusions into every part of our life from the family to the national budget….But Sabbath is not only resistance. It is alternative…The alternative on offer is the awareness and practice of the claim that we are situated on the receiving end of the gifts of God.”

- Walter Brueggeman, Sabbath as Resistance: Saying No to the Culture of Now

All the wise people I know, be they in the annals of recorded history or partners in contemporary living, practiced Sabbath and still do. Yet, I also know many people who resist taking sabbath time.

There is an apocryphal tale about Carl Jung and one of his patients. The man, somewhat melancholy and in the throes of a midlife transition, came to Dr. Jung. After describing his malaise, Jung told him to go home and spend one hour alone a week. The man arranged with his family that he should not be disturbed during his hour alone. The first week went splendidly, and the man found new energy. The second week found the man agitated after forty minutes, so he put some Beethoven on the phonograph and listened. In the third week, the man lasted 20 minutes before picking up a novel by F. Scott Fitzgerald. The fourth week, the man lasted all but ten minutes and rang up Jung for another appointment. In their session together, the man described what had happened. Jung responded, "I told you to spend one hour by yourself. I didn't tell you to spend time with Beethoven or Fitzgerald." To which the exasperated man exclaimed, "An hour? All by myself. Why, I'd go crazy." Dr. Jung replied, "You mean to tell me you can't spend one hour a week with the same person you inflict on everyone else the rest of the time?"

That's a hard tale for most of us to absorb—and one wonders if our resistance to Sabbath might relate to Jung's point.

Let’s bring this to a close on a more graceful note with the wisdom of the Nap Bishop, Tricia Hersey. Her book Rest is Resistance, and the accompanying deck of prayer cards reminds us of the value of sabbath rest as a form of resistance. "Rest Is Resistance is a call to action and manifesto for those who are sleep deprived, searching for justice, and longing to be liberated from the oppressive grip of Grind Culture."

This past Sunday, while visiting Gloria Dei Lutheran Church in Providence, Rhode Island, I shared with them the good news of the Sabbath and distributed cards from the Rest Deck. This multicultural congregation appreciated the message of Sabbath as resistance. One card struck a chord with a member of the community. She approached me after worship and showed me the card she drew from the deck. It read, "I am not a Machine, I am a Child of God. I will rest knowing that." She said, "Amen to this, amen to sabbath as resistance."

Until next time, I hope you can find rest.